A few years ago, I visited rue Didouche Mourad. I had just landed in Algiers for the first time. In the cab, an old German car, we drove for several seconds alongside a vast building site. To my astonishment, the driver pointed out that "the government is building Africa's largest mosque here".

As I explored the series of metabolic monuments photographed by Morgane and Simon, I discovered the Algiers mosque in a completely different landscape. It seemed as if the Grande Mosquée had irrevocably altered the vast bay with its imposing minaret. At the same time, the photographs revealed new urban situations, as many narratives between the twilight of the Bouteflika era and the dawn that the Algerian people are waiting for. Algiers was far away; the borders were still closed, confining Algerians even further. During my stay, I hadn't met a single witness to these three years of failed revolutions. One Sunday afternoon, through Djamel's intermediary, I called Tinhimène, a young Algerian architect. From her car, she told me how inexorably the mosque had become part of the landscape. Its construction had sidelined a young generation of Algerian architects. By the end of our conversation, it seemed that the preservation of the Algerian landscape was surely at stake elsewhere, between the preservation of the Casbah and the expansion of the city.

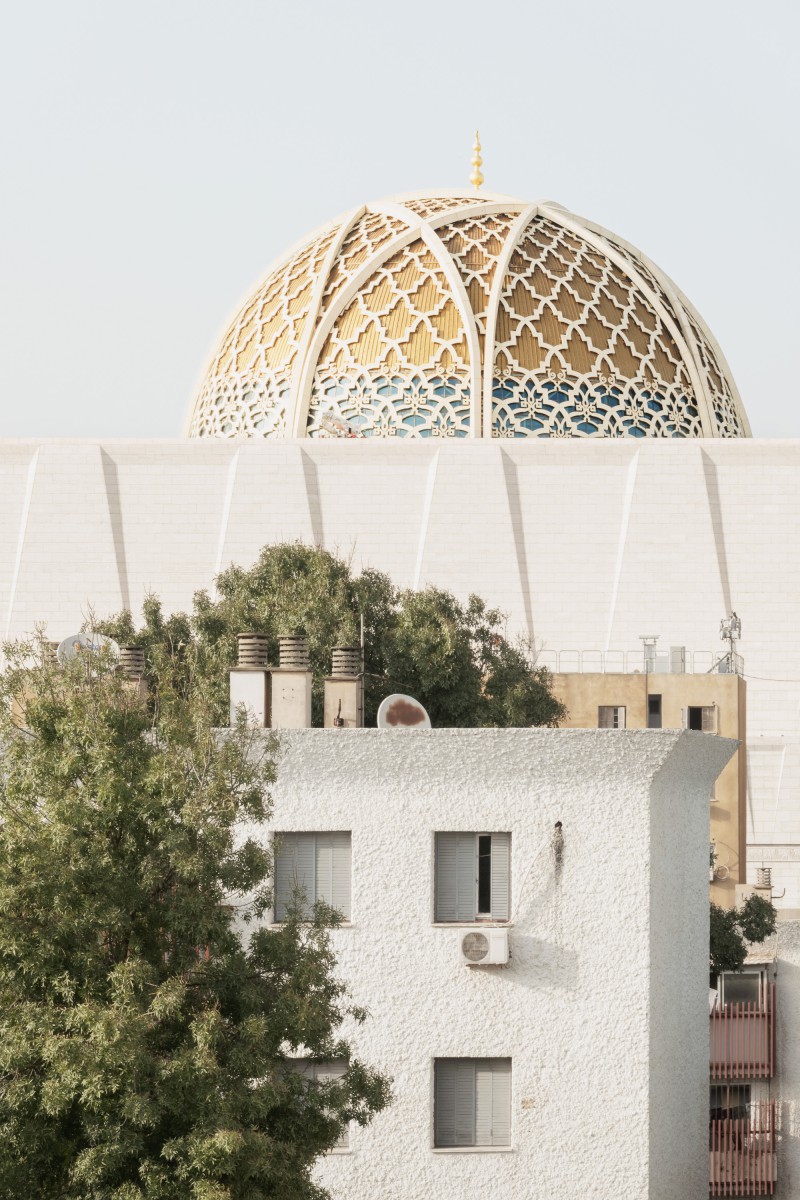

The bay of Algiers is built in a landscape of accumulation from the Casbah to the heights. The city is surveyed from top to bottom, with a few openings providing a view of the landscape. To mark its power, monuments have always sought height. The Aurassi Hotel and the Martyrs' Monument on El Madania hill emerge not only from Algeria's history, but also perpetually from the landscape. To reassure myself, I wanted to explore Algiers through its architectural modernity and its colonial period. Fernand Pouillon had the merit of giving me a taste for decor. Educated to regard ornament as a crime, the notion of style is uncomfortable, as it always takes the risk of expressing taste. The Grande Mosquée, with its vocabulary of Arab-andalusian or Islamic modernity, remains inaccessible. We inevitably look at it from the outside. They only hint at its ornamental richness, a showcase for Algerian know-how. Perhaps the project lies within.