Architecture as an Argument—There are 199 steps leading up to the second floor, where everything appears to be a bit different. Enveloped by a distant wall of prefabricated buildings, the industrial area around Herzbergstrasse rests like an island in the city. The TV tower stands in the west behind the slabs surrounding Landsberger Allee. In the east, wind turbines loom among the concrete panels of Marzahn. They mark the apparent periphery of the city, closer today than it was a few years ago.

Less than ten years ago, Lichtenberg still felt far away. In terms of the growing real estate industry, at least, which had concentrated on Berlin's centre thereby shaping our understanding of the city. Equally foreign was the notion to build something other than the one-story halls of the Pakistani and Vietnamese wholesalers that still distinguish the area around Herzbergstrasse today. No one was willing to invest in a ruin project in Lichtenberg.

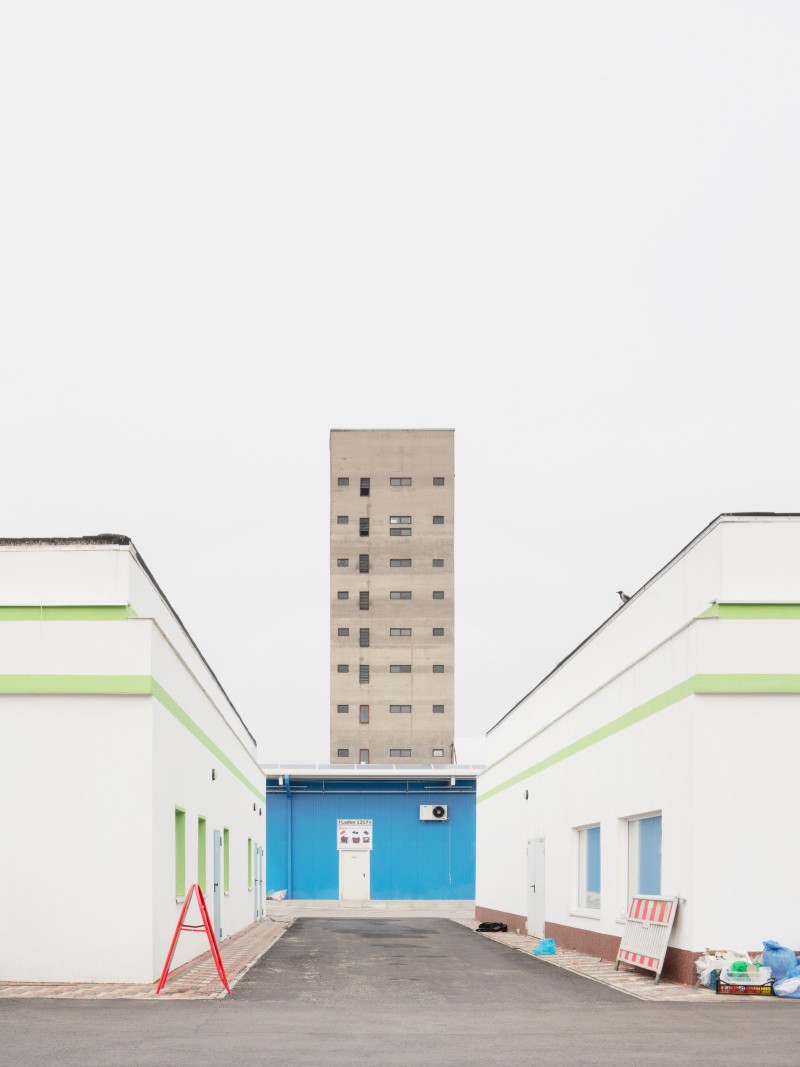

The ruins, that is the two towers of the former VEB Elektrokohle Lichtenberg. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the grounds were left unused until they were privatized at the end of the 1990s in an effort to fill the state's treasury. The former production facility was demolished leaving only the two concrete towers standing due to the high cost of demolition. Repurposing made no sense from a financial perspective, and so the towers remained closed and vacant.

Looking back on this short history today, it becomes clear how quickly the perception of a place and its architecture can change. After all, the present includes not only a place's past but also its past futures. Including what people thought a place stood for and could be. The two towers, for instance, are not only structural ruins but the remnants of a past idea of the future. Of ideology and strength, of technology and economy. The fall of the Wall not only put them out of use but also removed them from their time and their narrative. The idea of the place changed: failure.

This is what we set out to change meaning the first architectural intervention was not a structural one. With the goal of making a subsequent use of the towers conceivable and possible, their meaning would have to be loaded to open up the imagination beyond Berlin's ruin chic. This is how the story "San Gimignano Lichtenberg" came into being, based on the small Italian town in Tuscany, which is known for its (gender) towers. In this way, the idea of the town continues to develop. This does not only apply to these two towers. As a part of the industrial area around Herzbergstraße, this place is in a state of flux.

Gazing out from the second floor today, one can't help but think about the future. In the face of the current situation, it has become difficult to continue functioning as before in this altered present. Time has sped up, once again. The two towers stand as a symbol of that, of the transformation of seemingly alternative values and structures: of political systems, economic models and of environmental awareness. The recent crisis was not the first to show us how quickly local and global economies can potentially change. Entire economic sectors thrived, were disrupted or completely reconfigured. But our present also marks a moment of stagnation. The urgency of the issues that define our coexistence makes fundamental and structural change inevitable. The present has thereby refuted the notion of no alternative. Human paradigms and cultural values are not a matter of fact but are inscribed in the social, economic and legal frameworks that structure our daily lives.

Anyone standing up there, at the epicentre of friction between rezoning policies, zoning regulations, and changing perspectives on the city, inevitably faces the question: how will we live together? Price and development pressures from the centre have long existed and continue to intensify. The question of growth in our cities, in times of recent global crises - between economy and production, ecology and new models of living - causes us to reassess. How can we as architects act spatially to counter speculative construction, social and spatial segregation, resource exploitation, and technological escalation? What new strategies can we adopt for a common and better future?

Who speaks of the future must not evade responsibility: Skin is in the game - you have to risk your own skin. In all seriousness, what one portrays and articulates should not be an escape from the present, but a sharpening of the discussion, a question to raise or even an answer to anticipate in speculation.

"How can we, as architects, design not only the thing but also its origin in our society? " If one follows this thought, the meaning of speculation in architecture shifts away from a purely economic to a design idea. The object and its form are no longer in the foreground. The design is integrated into the concept of financing, operation and maintenance, use in the present and in the future. These factors, not either or, but both/and, become a visible part of the design, and architecture thus becomes an instrument for the change that has long since begun.